|

|

|

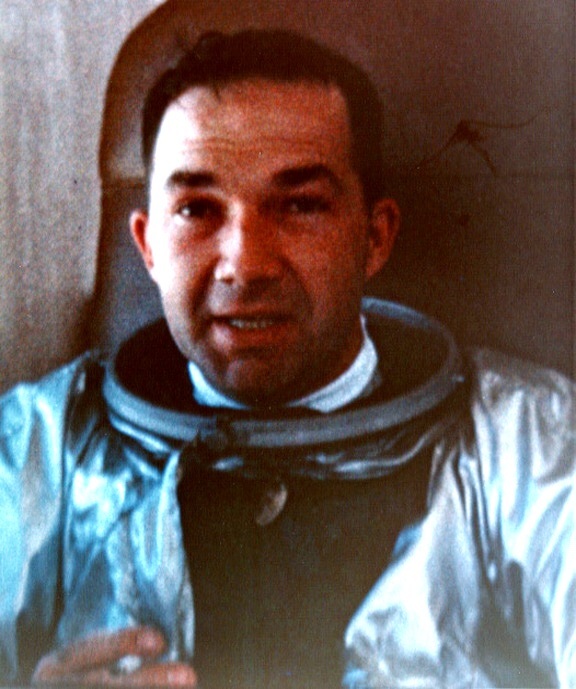

Jack Weeks, University of Alabama graduate and Birmingham native, died in service to his country. Reports from his most famous mission wound up on the president's desk during one of the flashpoints of the Cold War. His widow accepted his medal for valor shortly after his death. But for 40 years, nobody knew what he'd done. Only his wife knew he was a hero.

Jack Weeks, University of Alabama graduate and Birmingham native, died in service to his country. Reports from his most famous mission wound up on the president's desk during one of the flashpoints of the Cold War. His widow accepted his medal for valor shortly after his death. But for 40 years, nobody knew what he'd done. Only his wife knew he was a hero.

'It was only hard in that I was so proud of him,' said Weeks' widow, Sharlene Weeks, of her 40 years of silence. 'To have been able to talk about that would have helped me through my grieving process. I couldn't and I knew I couldn't. I couldn't even tell my children. I couldn't tell his mother and father. They died without ever knowing what Jack did.'

Weeks was a pilot in the Central Intelligence Agency flying the super-secret A-12 high-level surveillance aircraft from 1963 until his death in 1968. A couple of weeks before his death, he became the pilot who located the USS Pueblo, the American intelligence-gathering ship, after it was captured by North Korean patrol boats. The incident pushed the U.S. dangerously close to a confrontation with the communist country.

Next month, Weeks will finally get the public recognition he was denied for so long. Battleship Park, home of the USS Alabama, will commemorate the 40th anniversary of his death on June 4 with a ceremony that will include an Alabama Air National Guard fly-over.

The next day, some of Weeks' fellow pilots will take part in a symposium allowing the public to talk to men who were silent about their government work for decades.

'We like to highlight all Alabama veterans,' said Owen Miller, property manager and purchasing agent for Battleship Park. 'Here's this guy from Alabama. Even though it wasn't on a combat mission, he died serving his country. He's never been recognized.' Miller hopes Weeks' friends, classmates and fraternity brothers will attend the ceremonies.

'I didn't know it, didn't know any of it until after he was killed,' said Sharlene Weeks, 73, now an ordained minister in Massachusetts. 'What we were told was that he was working for Hughes Aircraft. His explanation to me was that he was leaving the Air Force and he would take a private job.'

So secret was her husband's work that Sharlene Weeks had to return to the CIA the Star for Valor she accepted on his behalf after his death.

Weeks and the former Sharlene Fenn were high school sweethearts. He graduated early from West End High School in January 1951 and enrolled at UA, where he majored in physics, joined Delta Chi fraternity and took part in ROTC.

In 1953 he married Sharlene, who had been attending Howard College, now Samford University. They moved into married student housing on the old Northington Hospital grounds where University Mall is now located.

'They were old army barracks and there were cracks in the floor that you could see through,' Sharlene Weeks said, laughing. 'It still had old army bunks.'

Weeks worked as a janitor on campus while his wife held a job in the Sears credit department. They played cards with the other married couples when work and study allowed and enjoyed themselves thoroughly, the way couples do when they're young and poor.

He graduated in 1955 and was commissioned a second lieutenant in the Air Force right out of college. Always interested in flying, he was given the helm of the new F-100 Super Sabre, the Air Force's first supersonic jet fighter.

Military life was a good fit for Weeks.

'He was what we'd call a man's man,' Sharlene Weeks said. 'He loved to hunt and fish. He loved to watch stock car races at the fairgrounds. He loved to take things apart. He was very mechanically inclined.'

Weeks thrived in the Air Force and after serving as a fighter pilot in Germany, became an instructor in the fighter weapons school at Nellis Air Force Base outside Las Vegas. He was also the general's personal pilot and seemed destined to be a career officer.

And then one day he told his wife he was resigning his commission to take a job with Hughes Aircraft. In truth, military officers have to resign their commission to become CIA agents.

Sharlene Weeks knew there was an air of secrecy around what they were doing. They told their friends and their children that they would be going to Washington, D.C., for an assignment. But when they left the base, they turned west toward California. When their sharp-eyed son pointed out they were traveling in the wrong direction, the kids learned they weren't going to Washington.

Once they arrived in California, Weeks underwent extensive testing. And psychologists examined the family.

'I thought and I believed Jack thought we were being vetted for the astronaut program,' Mrs. Weeks said. 'We had friends who were in the astronaut program.'

A casual observer might look at the A-12, the plane that Weeks flew, and mistake it for the two-seater SR-71 that could fly three times the speed of sound. Both employed similar technology and were nicknamed 'blackbird.' The A-12 was built to fly over the Soviet Union and gather intelligence, although it was never used for that.

'The State Department was always terrified that one of these would be shot down and it would be an international incident,' Miller said.

Weeks couldn't tell his wife anything about his new job.

'I didn't know what he was doing,' Sharlene Weeks said. 'I didn't know what he was flying. I just knew that he was flying.'

And that made Weeks happy. 'I always knew when he wasn't flying because he was grouchy,' she said. 'The only time he wasn't happy was when he wasn't flying.'

The Weeks family appeared to live a normal suburban life. But on work days, Weeks drove to Lockheed in Burbank, where he flew to the infamous Area 51 on Nellis Air Force Base.

The notion that a man could work in such secrecy that his wife would be completely unaware of it wasn't such a stretch for a military wife.

'You don't talk because it could be dangerous,' she said. 'You don't talk about that to the other wives. You share families and children. It was your way of life, the military life. Military wives don't talk about their husbands' jobs or they don't get promotions.'

Both she and her husband loved the military lifestyle, even though it required that she accept the danger inherent in her husband's job. In Germany, she lived with midnight air-raid scares. She saw her husband jump into his flight suit, run for the door and tell her to be ready to evacuate on a moment's notice.

'As a military wife you learn to live with that,' she said. 'They go out to fly every day and they can be killed any day. You've seen that happen to friends and you learn to accept that. They teach you to cope with that.'

She also knew how her husband felt about his job. 'I knew he felt strongly,' Sharlene Weeks said. 'One of his best friends had been shot down over Vietnam and was MIA. Another friend of his was killed over North Vietnam.'

Weeks flew missions over North Vietnam and when the North Koreans captured the Pueblo and took its crew prisoner, he got the intelligence his country needed.

At the same time, Congress was debating the future of the A-12 program, which it considered redundant. Congress decided to cut the CIA program and leave the Air Force program intact.

Weeks learned of his program's demise and decided to return to the Air Force, going back as a very young lieutenant colonel at 37. It seemed like a career track that might eventually put a star on his epaulets.

But he was slated to make one more flight in the A-12. Even though the planes were about to be stored, a new engine had been installed in Weeks' A-12 and it was his job to test it.

He called his family from Okinawa, Japan, on June 1 to wish one of his kids a happy birthday. It was the last time he spoke to him.

On June 4, 1968, according to the official record, Weeks was over the South China Sea between Okinawa and the Philippines. The telemetry sent from his aircraft back to the ground indicated his engine's inlet temperature was too high.

And then the aircraft ceased to send data.

Investigators believe the engine overheated and the plane exploded. Perhaps it happened so fast that even a pilot of Weeks' caliber couldn't correct it. There is no way to know for sure, because the plane apparently disintegrated.

'They think it impacted the water,' Miller said. 'When you impact the water at Mach 3, there's not a whole lot left. In fact, they never found anything.'

Shortly after her husband's plane disappeared, Sharlene Weeks got the call.

'When it did happen, it was, "This really can't be happening to me." she said. 'But yes, this does happen. It was hard to believe. He was overseas and I hadn't seen him in several weeks.'

It was then that Sharlene Weeks found out for the first time that her husband was in the CIA.

'I was surprised that I had never figured it out,' she said. 'I think I was busy raising the children, doing my job and I knew he couldn't talk about his. We shared other things in common but we didn't share that.'

About three weeks after Weeks' death, the CIA took all of the wives of A-12 pilots to Palmdale, Calif., to see the last A-12 land.

'It was so impressive,' Sharlene Weeks recalled. 'It was such a big plane for one man to fly. They brought it in right at sunrise. It was a beautiful experience.'

The CIA held a luncheon where Sharlene Weeks accepted her husband's Intelligence Star for Valor. But his job was so secret, the agency kept the medal for another six years before giving it to her.

'I never thought of him dying because of the Vietnam War, but that's exactly what it was,' Mrs. Weeks said. 'He was a casualty of the Vietnam War.

Unlike the wives of other Vietnam War dead, she couldn't tell the world about her husband's sacrifice for his country. Her children were already grown before they knew what their father had done.

'It wasn't until last September that we were allowed to talk freely,' she said.

In the meantime, Sharlene Weeks went back to college and got her bachelor's degree. She eventually went to seminary and became an ordained minister. The desire to be near grandchildren eventually led her to Massachusetts where she serves as a chaplain in a hospice.

Last September, the A-12 pilots were recognized at CIA headquarters on the agency's 60th anniversary. A restored A-12 was dedicated on the headquarters' grounds and an A-12 painting unveiled. Sharlene Weeks was there.

She plans to be at Battleship Park for the ceremony in June, and hopes some of her husband's friends and fraternity brothers will attend. She said she'd particularly like to see Ben Saltzman, the best man from their wedding.

She said someone recently mentioned that she would finally get her '15 minutes of fame.'

'I said, "This is not my 15 minutes of fame," she said. "This is Jack's. I didn't do anything.' I'm so glad people can finally know what he did.'

Reach Robert DeWitt at robert.dewitt@tuscaloosanews.com or 205-722-0203.

|

|

|