|

|

|

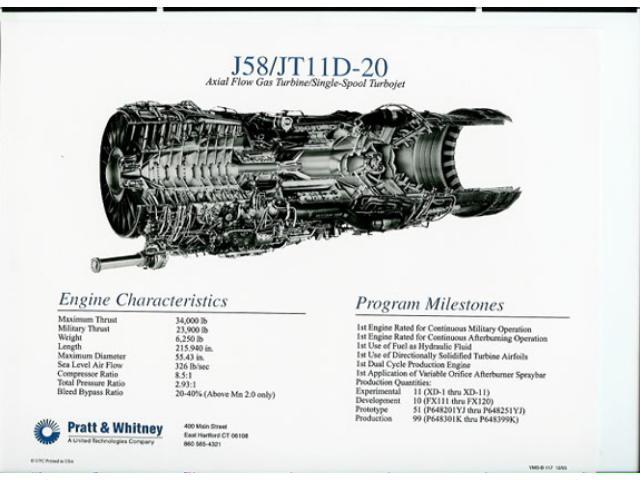

THE COMPANY AND ROADRUNNERS WHO BUILT THE J-58 ENGINES

POWERING THE A-12 ARTICLES OF PROJECT OXCART AT GROOM LAKE

AND OPERATION BLACK SHIELD IN OKINAWA

The role of Pratt Whitney in Project Oxcart, like that of all the other support companies, has remained shrouded in secrecy until recent years. Only now, after the CIA declassification of our activities, and even our existence, can the role of these Roadrunners be told.

It remains unknown the exact number of engine failures during the ground development and flight test phase of the J-58 engines of the A-12, YF-12, and their successor, the SR-71 Blackbird, but it was a lot. Many were minor and many catastrophic where the engine would be destroyed. For instance, if the failure was a compressor blade, it would likely take out many components downstream. If there was an afterburner liner failure it would just likely blow out the rear and do lesser damage. When all failures are included the number would be quite high. In terms of catastrophic failures, the number would be a lot less.

There were many engine teams at Pratt & Whitney. Many of them experienced catastrophic engine failures during a high mach tests. Until now, about all that is known about the trial, error, and successes of these unknown aviation pioneers has been a couple of test cell photos showing the afterburner shock waves. As this web page develops, stories about some of these engine failures during test cell tests will be told along with the many stories of success.

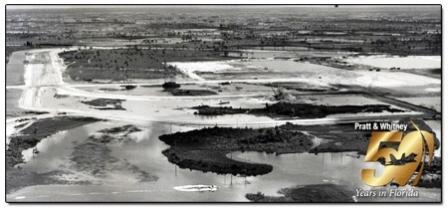

GOLDEN ANNIVERSARY - 1968

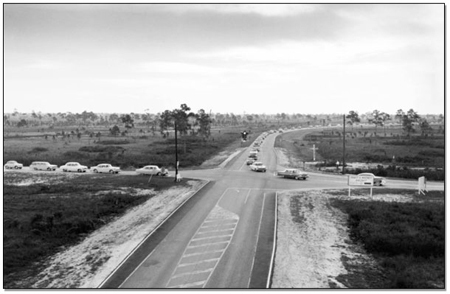

The landscape has changed drastically in the 50 years since Pratt & Whitney officially dedicated its new Florida facility (designated the Florida Research and Development Center) on May 27, 1958. If you could step back in time and survey the land for the first time, just as the first company officials did more than 50 years ago, you might be taken aback by what you would see, or more interestingly, what you wouldn't see

There wouldn't be a gas station nor a race track; not even a traffic light. You wouldn't see the Beeline Highway because it doesn't exist yet, and you may well be surprised to find yourself standing knee-deep in water. So why on earth would P&W officials pull up their New England roots and replant them in a Florida swamp?

To fully understand this rationale requires a look back at our company's history

and an examination of the chain of events that led up to the

decision.

After World War II, P&W faced a serious dilemma. The gas

turbine jet engine was clearly the future of aviation; however, government

policy dissuaded the company from jet powerplant research by directing sorely

needed development funds to a rival engine manufacturer (General Electric).

Moreover, the commercial market for piston engines, P&W's chief product

line, was declining.

The company needed to act fast or face the possibility of going out of business.

In a bold move, United Aircraft Corporation, P&W's parent corporation at the

time, staked $15 million of its own money - nearly twice the value of its assets

at the time - on the development of a new and revolutionary gas turbine jet

engine.

The gamble paid off when P&W debuted its first gas turbine jet engine in

1948, the JT3. Success was cemented two years later when the Air Force selected

a JT3 variant, the J57, to power its B-52 bomber. In one broad sweep, P&W's

J57 jet engine effectively leapfrogged the industry in technology and

performance - producing more than 10,000 pounds of thrust, a feat previously

thought unachievable. The J57 went on to become one of the most widely used jet

engines in the world and, by the mid-1950s, firmly established P&W as

America's premier jet engine manufacturer.

Fueled by the J57's dramatic success, additional engineers were hired and

factories expanded, but it quickly became evident that the company's East

Hartford facilities were being stretched beyond their limits. Compounding the

problem was the fact that the company had been awarded contracts to develop two

new and highly-classified military engines - the J58 and the 304. The J58 was a

turbojet engine and the 304 was a liquid-hydrogen fueled engine code named

'Suntan.'

Testing these clandestine engines presented the greatest challenge because of

the heavy population surrounding the main plant in East Hartford; clearly the

experimental engines' roar had to be muffled. Furthermore, protection was needed

from volatile fuels such as liquid hydrogen. To stay put in New England would

require the construction of new, and expensive, test cells.

Testing these clandestine engines presented the greatest challenge because of

the heavy population surrounding the main plant in East Hartford; clearly the

experimental engines' roar had to be muffled. Furthermore, protection was needed

from volatile fuels such as liquid hydrogen. To stay put in New England would

require the construction of new, and expensive, test cells.

In addition to plant overcrowding and a need for test facilities, the

highly-classified government engine programs called for increased security. At

the same time, the company was having difficulty recruiting engineers locally.

Company officials concluded that the best solution would be to build a new

facility outside of Connecticut. The question was where?

Florida had two advantages. First, Florida state officials, hoping to recruit

high tech companies to augment their fledgling economy (primarily tourism and

agriculture), offered to help P&W find a suitable location. Second, a

favorable 30-to-one Florida job applicant response ratio over similar positions

offered in New England sealed the deal.

The company selected a 7,000 acre tract in a remote area of Palm Beach County

that was part of a state-owned wildlife preserve. To obtain this land the

company purchased 9,000 acres nearby and exchanged it with the state. This

increased the preserve by 2,000 acres and, simultaneously, provided the company

with a large plant site surrounded by an even larger wildlife preservation area.

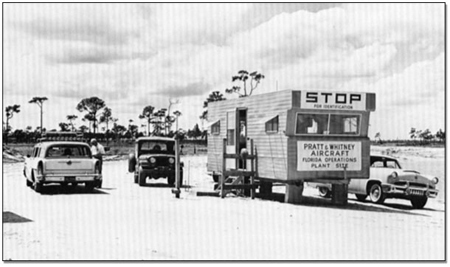

On Nov. 1, 1956, a small staff opened P&W's Florida Operation in a leased

office in a downtown West Palm Beach building located on Datura Street. The

staff rapidly expanded to 825 employees before the end of 1957.

'When we first bought a chunk of this wild Everglades country, people began to

realize the world of Buck Rogers was about to change from a dream to a reality.'

? Bill Gwinn, President United Aircraft Corporation

The 1950s brought a flourishing economy to America.

Emerging from the tumultuous decade of World War II, people started to enjoy

life again. Unfortunately, all was not rosy. The Soviet Union, our ally in the

war, was now considered a grave threat because it also had 'the bomb.'

Ironically, the weapon that helped end the war had also begun a new one, the

Cold War. Both countries were scrambling to develop missiles to deliver nuclear

warheads and rockets to place payloads in orbit. The space race was on and the

Russians were ahead at the first lap with the launch of Sputnik. Barely the size

of a basket ball, the satellite carried only a simple transmitter, but its

monotonous beep sent a chilling message to Americans.

With increasing Cold War tensions, the U.S. was eager to acquire intelligence on

Soviet military capability. At issue was the fact that existing surveillance

aircraft, mostly converted bombers, were vulnerable to anti-aircraft artillery,

missiles and fighters. Furthermore, the nation's chief surveillance aircraft,

the U-2, was capable of flying at high altitudes well above the reach of Soviet

fighters, but its slow speed made it an easy target for Russian missiles.

It became apparent that America needed a superior reconnaissance platform and in

1956 Lockheed's legendary aircraft development incubator, known as the 'Skunk

Works,' designed just such a plane, the CL-400. In turn, Pratt & Whitney was

recruited to develop the aircraft's radical new engine, the liquid

hydrogen-powered 304. This highly-classified project was code named 'Suntan.'

Hydrogen-fueled 304 Suntan engine

Not having any prior experience with liquid hydrogen, a super-cold

substance that boils at minus 423 degrees Fahrenheit, there was much for Pratt

& Whitney engineers to learn. More sobering, hydrogen had a nasty reputation

for extreme volatility, conjuring up visions of the Hindenburg disaster.

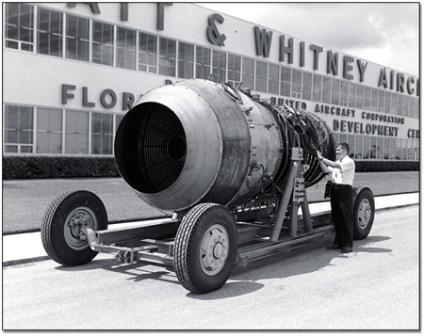

At the same time, another classified program was under development for the U.S.

Navy's new Mach 3 reconnaissance plane. The high speed spy aircraft required the

development of the most powerful jet engine yet; what was to become Pratt &

Whitney's J58.

These two highly-secretive programs were initially managed in East Hartford,

Conn., however, that facility's lack of space, noise containment and security

quickly made it apparent that another location was needed. In a bold move, the

company made the decision to relocate the development of both the J58 and the

304 to West Palm Beach, Fla.

West Palm Beach's first general manager, Chuck Roelke, was faced with the

daunting task of making the move work. Exacerbating the situation, the company

would not part with its experienced employees that Roelke desperately needed.

Therefore, he was forced to recruit his workforce outside of the company. At the

same time, the customers wanted their engines to progress as quickly as

possible, and consequently, work had to begin in makeshift shops.

The J58 engine at test.

During the months that followed, plans were made to

construct a 600,000 square foot main building that contained both office and

manufacturing space. With no direct access to the site available initially,

development was intimidating. The state of Florida agreed to build a road (later

to become known as the Beeline Highway) but the segment from West Palm Beach to

the plant was delayed when the swamp refused to cooperate, swallowing tons of

fill and two bulldozers.

Despite the primitive conditions, spirits continued to remain high for Roelke

and his employees, and in September 1957, the Florida swamp's tranquility was

rocked by a roar that could be heard for miles - the bellow of the 304 engine's

initial test firing. Later that year on Christmas Eve, the J58 engine,

progressing equally well, underwent its initial run. Less than a year later, on

May 27, 1958, the site was officially dedicated as the Pratt & Whitney

Aircraft Florida Research and Development Center (FDRC). With construction

completed on the office, manufacturing and test facilities, and the engine

programs progressing well, success seemed guaranteed for the Florida site.

In the ensuing months the Air Force continued to invest in liquid hydrogen

production and the 304 logged more than 25 hours of run time. Then, in an

unforeseen chain of events, the Air Force, bowing to budgetary pressures and a

groundswell of opinion that a hydrogen-fueled aircraft was too dangerous and

expensive to maintain, decided to cancel the project. Landing a second blow, the

Navy terminated development of its attack plane, and subsequently, work on the

J58 ground to a halt after just a few test firings. Fate had turned the site's

apple cart upside down, leaving the company questioning the wisdom of its

Florida investment decision and Roelke's workforce pondering their future.

What the employees didn't know was that the setback would be brief and their new

facility was just beginning to blossom. The United States, still requiring a

long-range reconnaissance platform, had recruited Lockheed to design a new

plane, the A-11 (the prototype's design would later evolve into the famous SR-71

Blackbird). And to meet the demands of high altitude Mach 3 flight, the nation

once again turned to Pratt & Whitney and its J58 engine.

At the same time, America's growing need for space launch capability led the Air

Force to enlist Pratt & Whitney's newborn liquid-hydrogen expertise in the

development of a new upper-stage rocket engine, the LR-115. In 1961, the program

was transferred to NASA, and the engine became known as the RL10. The last 304

tests were still underway when RL10 development began. The transition was

seamless and the pulse of the company's progress never missed a beat.

Click on images to enlarge

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| PW Tales by Dr. Abernethy |

![]()

GET RID OF TURBINE ENGINES

Author: Bob McKellar

We gotta get rid of turbines, they are ruining aviation.

We need to go back to big round engines.

Anybody can start a turbine, you just need to move a switch from "OFF" to "START," and then remember to move it back to "ON" after a while. My PC is harder to start.

Cranking a round engine requires skill, finesse and style. On some planes, the pilots are not even allowed to do it.

Turbines start by whining for a while, and then give a small lady-like poot and start whining louder.

Round engines give a satisfying rattle-rattle, click-click BANG, more rattles, another BANG, a big macho fart or two, more clicks, a lot of smoke and finally a serious low pitched roar.

We like that. It's a guy thing. When you start a round engine, your mind is engaged and you can concentrate on the flight ahead. Starting a turbine is like flicking on a ceiling fan: Useful, but hardly exciting.

Turbines don't break often enough, leading to aircrew boredom, complacency and inattention. A round engine at speed looks and sounds like it's going to blow at any minute.

This helps concentrate the mind.

Turbines don't have enough control levers to keep a pilot's attention.

There's nothing to fiddle with during the flight.

Turbines smell like a Boy Scout camp full of Coleman lanterns. Round engines smell like God intended flying machines to smell.

I think I hear the nurse coming down the hall. I gotta go.

|

|

|