|

|

|

|

|

|

|

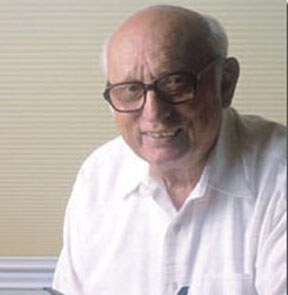

Carmine Vito:

U-2 Pilot

By Eric Hehs

Code One Magazine

The U-2 suspended from the ceiling of the Air & Space Museum in Washington, DC, carries a payload from one of its earliest flights: a small lump of chewing gum. "If you climb up the wing of the airplane, open the canopy, and reach under the left rail, you will find my wad of tutti fruitti," says Carmine Vito, one of the first six pilots trained to fly the high-altitude reconnaissance craft for the CIA. Vito stuck it there on 5 July 1956 before taking off from Wiesbaden, Germany, on his first operational mission.

"I was a little nervous," recalls Vito. "And my throat was dry." His anxiety could have been attributed to his mission route right over Moscow at the height of the Cold War.

Vito is the only U-2 pilot to fly directly over Moscow. His flight was the third operational flight over potentially hostile territory, or what the pilots called "hot" flights. Carl Overstreet flew the first such flight of the U-2 on 20 June 1956. The mission covered Poland and East Germany. Then Hervy Stockman flew over Soviet territory on 4 July, going as far north as Leningrad to photograph naval shipyards and then west to the Baltic States to cover jet bomber bases. The fourth, fifth, and sixth missions were flown by Marty Knutson, Glen Dunaway, and Jake Kratt. All were successful.

"The Russians launched planes to intercept Overstreet on the first flight," notes Vito. "But they couldn't reach him." Stockman's flight was also detected by Soviet radar. Several MiG fighters scrambled to intercept him, too. As with previous flights, the intercepts failed. Soviet fighters could not approach the altitude needed to shoot down the lofty U-2.

Vito's selection for the Moscow mission was more a function of circumstance than of design when the orders came to fly. The U-2 detachment at Wiesbaden was typically given an alert notice from headquarters twelve hours before takeoff. The notice usually came before five p.m. During those twelve hours, ground crew and pilots prepared for the flight. Lockheed, Pratt & Whitney, and Kodak crews conducted ground checks of the airplane, engine, and cameras. Pilots suited up in their specialized partial pressure suits and breathed pure oxygen to ward off the effects of rapid decompression (the bends). To purge nitrogen from their blood, U-2 pilots had to be "on the hose" for at least two hours before they were given the green light for takeoff.

"Without a go signal from headquarters, everyone headed for the club after five that evening," explains Vito. "On that particular weekend, the 4th of July, most everyone was celebrating. When the late go came down from headquarters, I was the only one who had had only one drink. So, even though our order of mission flights had been predetermined by drawing straws, I was selected for the mission."

After forty-six years of describing this particular U-2 mission, Vito can't be certain if he's telling the story from actual memories or telling it from memories of previous descriptions. Whichever the case, he remembers the firework display keeping him awake that night and the obligatory steak and egg meal early the next morning. "They always fed us steak and eggs before a flight," he says. "I didn't want steak and eggs at two in the morning, but they were on the checklist. So I had to eat."

Vito's route took him over Kracow, Poland, and then to Brest and Baranovici in the Ukraine. He stayed on this east-northeasterly route, overflying Minsk on his way to the Soviet capital.

The mission began in bad weather. "We had about 200 feet of visibility on the ground," recalls Vito. "The sky was clear at 3,000 to 4,000 feet, but I had undercast halfway inbound." The weather cleared as Vito followed a railroad line from Minsk to Moscow. At an altitude of more than 66,000 feet, he listened to Peter and the Wolf, a Russian musical composition with narration, transmitted from a Soviet radio station. Small mosaic fields of the collective farms passed below him. "Those fields reminded me that Russian farmers tilled the land by hand," he says. "I couldn't get mad at people who work that hard. I was never mad at the Soviet people themselves, just at their government."

Vito's mission took him directly over Moscow and its extensive network of newly built air defenses, which ringed the city in three concentric circles at twenty, forty, and sixty miles from the city center. A smoggy sky hid the city below. "My bubble burst," Vito recalls. "I thought, Gee I came all this way for nothing. But the filters on my camera cut through the haze. A year or so later, I learned that the resulting film picked up some remarkable detail."

According to a CIA history of the U-2, Vito's mission came back with images of the Fili airframe plant where the Soviets were building their first jet bomber (known as the Bison to the West); a bomber arsenal in Ramenskoye; a rocket engine plant in Khimki; and a missile plant in Kaliningrad. From just east of Moscow, he turned north to the Baltic coast and then back south to West Germany.

"I learned later that the Soviets launched at least five fighters to intercept my flight," says Vito. "Two planes took off initially. The lead plane aborted takeoff, ran off the runway, and exploded. The wingman went through lead's flames and then bailed out. Two more airplanes scrambled and were refueled in the air. Those airplanes got lost or collided. The pilots bailed out. A fifth plane scrambled but couldn't find the tanker. He was lost and never found to this day." Vito never received credit for five aerial victories. "After all, I never fired a shot," he says.

On his way back to West Germany, the Canadian radar came on the air: "Lone Ranger, this is Tonto. Keep heading the way you are going. You have twenty-two minutes to touchdown."

"I knew they were talking to me because they had the best radar around and had picked us up on previous flights," recalls Vito. "But U-2 pilots had to observe complete silence on the radio. To this day, I wish I could have replied, 'Ti Ee Kemosabe.'"

Vito accumulated about 450 hours in about sixty-five flights in the U-2 from 1955 to 1959. His last flight was in the first U-2C at Edwards AFB. He left U-2 headquarters at the CIA in August 1960.

Vito's mission over Moscow as well as previous and subsequent U-2 flights have gone largely uncelebrated for reasons of national security. Only recently have these details surfaced from CIA files made public. Public programs sponsored by the CIA have even included discussions with their counterparts from the former Soviet Union. What was once the domain of government officials with the highest security clearances has now become primary research for Cold War historians. Vito and others associated with the early days of the U-2 program are finally enjoying some deserved recognition and acclaim.

Explained George Tenet, director of the CIA, in a symposium on the U-2 in 1998: "From the U-2 data captured by our overflights, data that was corroborated by intelligence obtained by other means, President Eisenhower could confidently resist the fierce domestic pressure to engage in a massive arms buildup. He knew for certain, for certain, that we had no bomber gap and no missile gap with the Soviet Union, all Soviet boasting to the contrary. By any measure, that was an intelligence triumph. The men and women who worked long and hard and often took great risks for the U-2's early successes can be forever proud of that.

"I want to say a special thanks to the pilots," Tenet continued, "from Carmine Vito to the U-2 pilots of today. The courage that Carmine and his colleagues showed made an enormous difference to the security of our country. These men allowed generations of Americans to live in peace and prosperity. On behalf of all Americans, I want to thank you, Carmine, and all your co-pilots and colleagues, for your great and selfless heroism."

Today's U-2 pilots of the US Air Force carry on that legacy in missions just as critical to the security of the United States and of its allies.

Col. Carmine Vito flew the first mission over Moscow. On August 14, 2003 he spoke at the Daedalus Foundation gathering where his first-person description of his involvement in the U-2 program was warmly received. He was given a standing ovation by the flight. Flight Captain Col. Rick Ruddell presented Col. Vito a copy of "The Legacy of Daedalus" in appreciation of his talk.

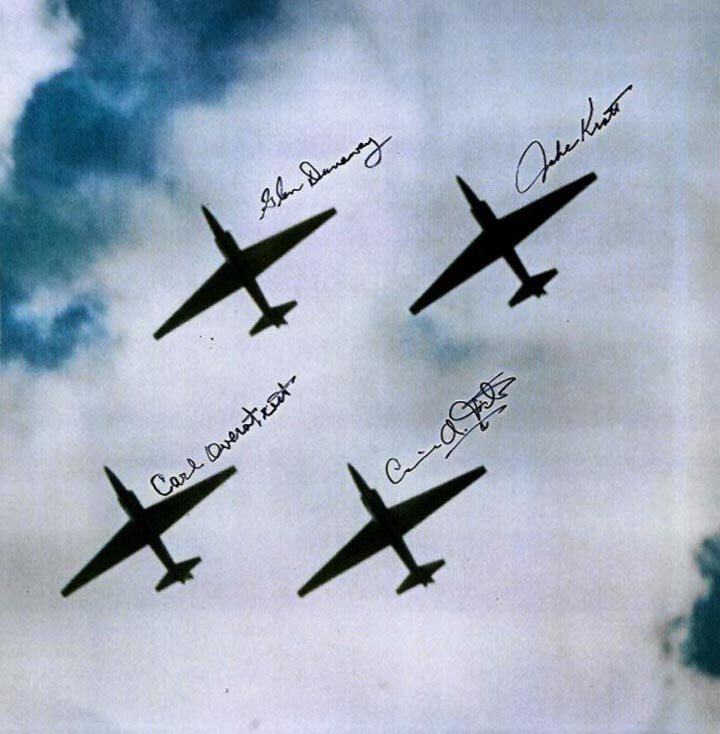

U-2 Diamond Formation

This photograph, made in Europe in 1957, shows aircraft of the first U-2 detachment to be deployed for operational use in intelligence gathering. On this particular day four aircraft were flown on shakedown flights, with take-off and landing times that resulted in their being airborne at the same time. The pilots, experienced fighter pilots, took this opportunity to exhibit the U-2 to ground personnel in a fighter show formation - the Diamond.

Lead aircraft, Glendon (Glen) Dunaway; right wing, Jacob (Jake) Kratt; left wing, Carl Overstreet; slot, Carmine Vito. This undoubtedly is the first - - and only - - four aircraft formation flown in U-2 airplanes.

Photo taken by Hervey Stockman

Austinite flew U-2 spy plane over Moscow for CIA during Cold War

By Kate Alexander

AMERICAN-STATESMAN STAFF

Saturday, August 30, 2003

For decades, the world knew nothing of Carmine Vito and his covert U-2 missions over the Soviet Union. That changed in 1998 when the Central Intelligence Agency declassified the details of the spy flights and their contribution to the Cold War.

"I want to say a special thanks to the pilots, from Carmine Vito to the U-2 pilots of today," CIA Director George Tenet said at a 1998 symposium on the U-2, the high-flying surveillance plane that debuted in 1956.

"The courage that Carmine and his colleagues showed made an enormous difference to the security of our country," Tenet said. "These men allowed generations of Americans to live in peace and prosperity."

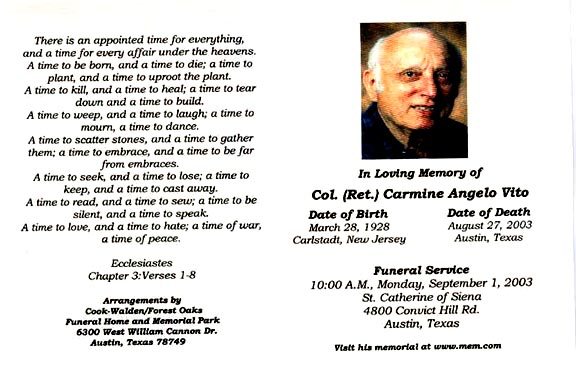

Vito, an Austin resident since retiring from the Air Force in 1977, died Wednesday of a stroke after heart surgery, his wife, Barbara Vito, said. He was 77. A funeral Mass is scheduled for 10 a.m. Monday at St. Catherine of Siena Catholic Church.

Vito, who flew 65 spying missions for the CIA, was the only American pilot to fly a U-2 reconnaissance mission directly over Moscow. That flight, on July 5, 1956, collected critical information about the Soviet military capacity. Vito's U-2 hangs from the ceiling of the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum in Washington, along with the Tutti-Frutti gum that he left beneath the canopy.

The CIA flew 24 missions over Russia between 1956 and 1960, when the loss of Francis Gary Powers' U-2 plane halted them.

Glen Dunaway, also an Austin resident, was one of the first group of six pilots, along with Vito, to operate the U-2. Dunaway remembers Vito as an ebullient and thoughtful man who was always ready to fly.

"It was a very big deal, and everybody knew it," Dunaway said of their missions. They also knew the dangers of a "mission when you fly in somebody else's back yard and they don't like it. You have to treat it with maximum respect and professionalism."

The photos taken from the U-2 provided the first verifiable data about the Soviet Union's military capacity and was used to debunk rumors that the Russians were much stronger than they turned out to be.

"It was the beginning of a program that allowed the U.S. to have a much better understanding of what was going on in the Soviet interior," said Jeffrey Richelson, a senior fellow with the National Security Archive at George Washington University. Accurate information about the Soviet military laid the groundwork for future arms treaties, Richelson said.

Vito met Barbara at CIA headquarters, where she was an administrative assistant. They married in 1960 and had four children. Vito spent the remainder of his career in the Air Force, retiring as a colonel.

Because Vito did not speak of his covert missions, people knew him for his humor and outgoing nature rather than his role in the Cold War. That is why he will be missed, Barbara said.

Sad to see an old warrior like Carmine lay down his sword. He will not soon be forgotten. I probably took Carmine on his last flight in an airplane in Oct. 2002. He attended the Daedalian Flight Line meeting at San Marcos last year and won one of the raffles for a flight in a T-6. Carmine came to me and said he didn't want to fly in the T-6 but would rather fly in the 1948 Super Swift I was flying. I arranged a swap of airplanes for him and took him on a flight in the local area. He related that he had owned a Swift in the middle fifties and always liked the airplane but had not flown one with the big engine. It was my pleasure Carmine.......

Sad to see an old warrior like Carmine lay down his sword. He will not soon be forgotten. I probably took Carmine on his last flight in an airplane in Oct. 2002. He attended the Daedalian Flight Line meeting at San Marcos last year and won one of the raffles for a flight in a T-6. Carmine came to me and said he didn't want to fly in the T-6 but would rather fly in the 1948 Super Swift I was flying. I arranged a swap of airplanes for him and took him on a flight in the local area. He related that he had owned a Swift in the middle fifties and always liked the airplane but had not flown one with the big engine. It was my pleasure Carmine.......

Col. Ed Lloyd USAF, Ret.

CARMINE VITO

An Appreciation

All tales grow with the telling. And when your life had so many tales worth telling, as did that of Carmine Vito, then I suppose it was inevitable that some would grow out of proportion. Thus it was with "The Lemon-Drop Kid." The story goes that, when flying the U-2 spy plane on a vital, top-secret mission for the CIA, Carmine reached into his flying suit for one of his favorite sweets. Only when the "sweet" reached his mouth, did Carmine realize that he had fumbled in the wrong pocket. Instead of the lemon drop, he had extracted the cyanide pill which his employers had thoughtfully provided, in case he was shot down, captured, and tortured. After months of planning, one false move had nearly sabotaged America's audacious plan to prise apart the Iron Curtain and learn the Soviet Union's military secrets!

I don't think that Carmine was responsible for this amusing, but inaccurate, tale. He always denied it. But with some reluctance, I sensed. For Carmine had a particularly dry sense of humor, and a sharp sense of the ridiculous. He knew that life - his own included - was a theatre of the absurd. This outlook provided me with some fascinating and unusual perspectives, as I explored the U-2 story with him on a number of occasions during his retirement.

He described crash-landing on the dry lake at the test site and collapsing the landing gear. When the unsighted controllers in the tower asked him to state his position, Carmine replied "Horizontal, no ladder needed, but send out a truck as it's a long walk back!" He told how he was chosen by default for the mission to overfly Moscow, when the alert came during an Independence Day party where he was the least inebriated participant. Later, in U-2 project headquarters, he discovered that another overflight to photograph denied territory was being planned for the same day as a solar eclipse!

When the CIA celebrated the U-2 at a 1998 conference in Washington, I remember Carmine's reaction when we discovered that the Agency had finally released its own history of the program, but with all the important places and names blacked out - including his own. Rather than being annoyed that his contribution was once again being suppressed, he was simply amused by the ludicrous rationale of the censors.

Well, Carmine, you can rest assured that your place in Cold War history has been properly documented. You were part of a unique group, who served their country well. You were all a little crazy, but the best that there is.

Chris Pocock

Author, THE U-2 SPYPLANE - TOWARD THE UNKNOWN

and DRAGON LADY - THE HISTORY OF THE U-2 SPYPLANE

|

|

|